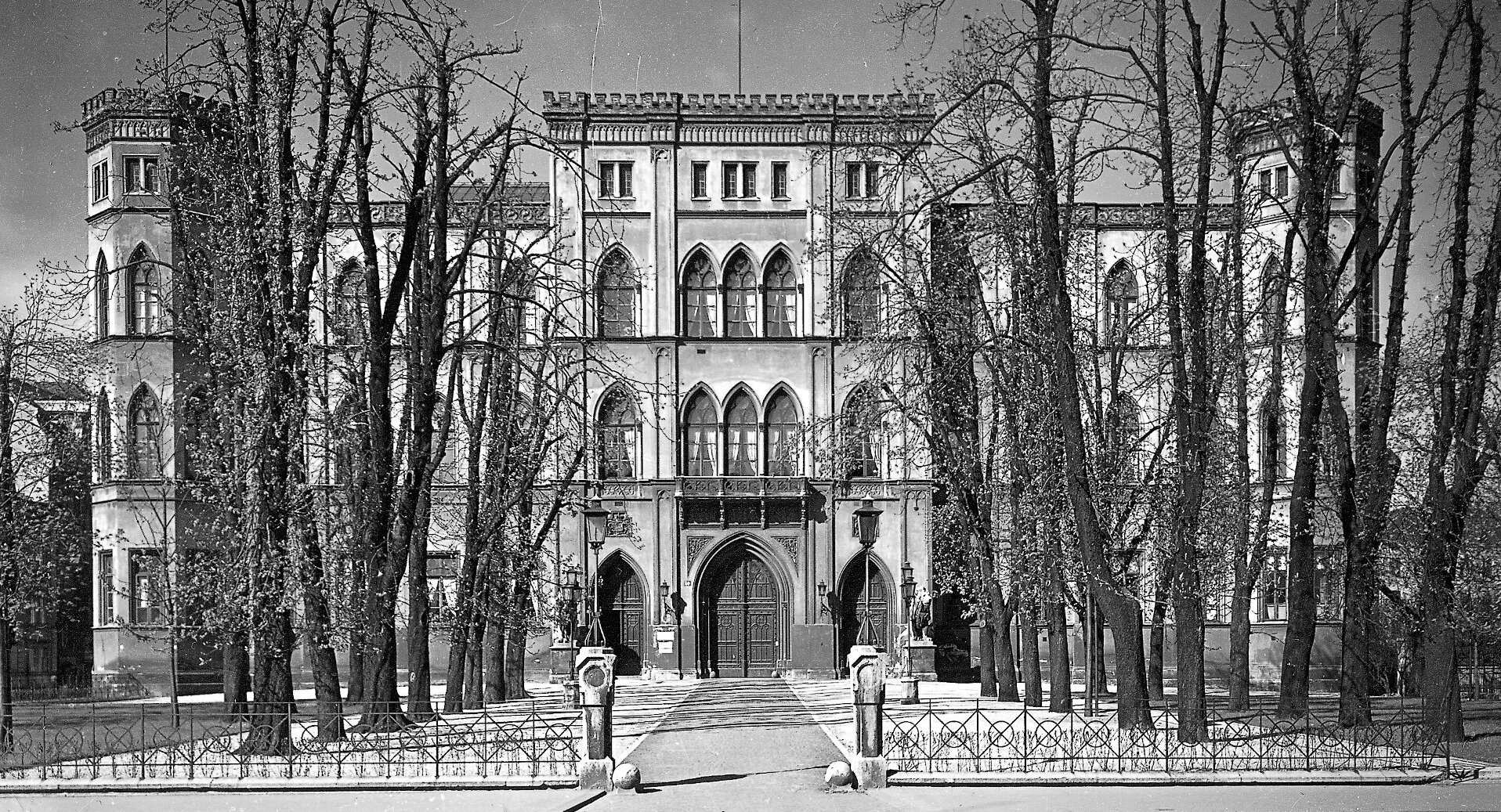

In a meeting at the Hofbräuhaus beer hall in February 1920, Adolf Hitler announced that the Party would change its name to National Socialist German Workers’ Party (NSDAP) and he outlined its first manifesto. When he became Party chairman in July 1921, he stated that “Munich is the headquarters of the movement and always will be.” With a rapidly growing membership, the Party moved its main offices to the Gasthaus Cornelius inn at Corneliusstraße 12. By the end of 1922, the Party leadership in Munich was able to count 100 local branches throughout Germany, the majority of them in Bavaria.

After the failed putsch of November 1923, the NSDAP was initially banned. It was newly founded in February 1925 under the same name, but pursuing a line that was allegedly legal. The Party headquarters remained in Munich. Between 1925 and 1930 they were located in a rear building in Schellingstraße, very close to the studio of Hitler’s personal photographer, Heinrich Hoffmann.