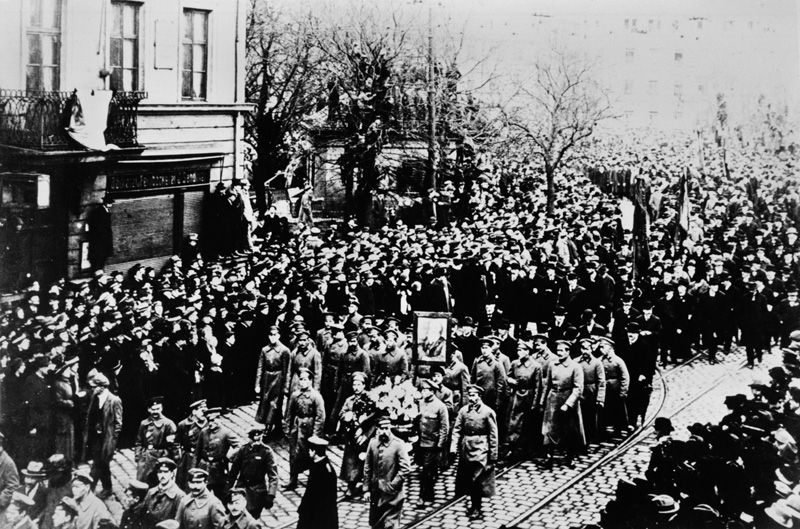

Mitte Februar 1919 war Kurt Eisner, Ministerpräsident und bayerischer USPD-Vorsitzender, politisch gescheitert. Zur fortwährenden Kritik seitens der politischen Kontrahent*innen auf der rechten wie auf der linken Seite kam, dass ihn nun auch der Koalitionspartner MSPD nicht mehr stützte. Am 21.2.1919 war er auf dem Weg zum bayerischen Landtag, um dort seinen Rücktritt zu verkünden, als ihn der Student und Offizier Anton Graf Arco auf Valley hinterrücks erschoss. Er begründete seine Tat mit den Worten: „Eisner [...] ist Bolschewist, ist Jude, ist kein Deutscher“ (Hitzer, S. 391).

Der radikalen Linken erschien das Attentat als ein Anschlag auf die Revolution insgesamt, sie machte Eisners sozialdemokratischen Kontrahenten Erhard Auer für den Mord mitverantwortlich. Der kommunistische Arbeiter Alois Lindner verübte noch am selben Tag im Landtag ein Attentat auf Auer und erschoss zugleich zwei Offiziere. Der Mord an Eisner geriet so zum Auftakt einer weiteren Phase der Radikalisierung des politischen Lebens in München, an deren Ende die Ausrufung der Räterepublik am 7.4.1919 stand.

Graf Arco selbst wurde noch am Tatort von einem Bewacher Eisners niedergeschossen und schwer verwundet. Der Prozess gegen ihn vor dem Münchner Volksgericht begann im Dezember 1919. Der vorsitzende Richter Georg Neithardt verurteilte ihn am 16.1.1920 zum Tode, fand aber zugleich anerkennende Worte, indem er ausführte, dass seine Tat „nicht niederer Gesinnung, sondern der glühendsten Liebe zu seinem Volke und Vaterlande“ entsprungen sei (Hitzer, S. 313). Das Todesurteil löste eine Protestdemonstration nationaler und nationalsozialistischer Gruppen, unter anderem an der Münchner Universität, aus. Es kursierte das Gerücht, sie würden im Verbund mit der Reichswehr einen Staatsstreich unternehmen, falls das Urteil nicht zurückgenommen werde. Tags darauf wandelte der bayerische Justizminister, Ernst Müller-Meiningen (DDP), das Todesurteil in eine lebenslange Festungshaft um. Diese wurde im Jahr 1924 aufgrund eines Ministerratsbeschlusses im Hinblick „auf spätere Bewilligung einer Bewährungsfrist“ (Hitzer, S. 315) unterbrochen. 1927 wurde er von Reichspräsident Hindenburg amnestiert.