Nach der nationalsozialistischen Machtübernahme in Bayern ernannte Reichskommissar Ritter von Epp umgehend eine neue Regierung. Gauleiter Adolf Wagner wurde Innenminister, der Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler wurde Münchner Polizeipräsident und Reinhard Heydrich, der Chef des Sicherheitsdienstes der SS, wurde Leiter der Politischen Abteilung der Polizei. Damit stellten die Nationalsozialisten, wie sich zeigen sollte, entscheidende Weichen für den Aufbau des nationalsozialistischen, von der SS beherrschten und durchdrungenen Polizeistaats, der ihre Herrschaft dauerhaft sichern sollte.

Die Bayerische Politische Polizei

Die Nationalsozialisten wussten um die große Bedeutung der politischen Polizei und ihr reichhaltiges Aktenmaterial. Himmler ließ sich deswegen von Innenminister Wagner zum „Politischen Polizeikommandeur Bayerns“ ernennen. Er gliederte die Politische Abteilung aus der Polizeidirektion aus und benannte sie zugleich in Bayerische Politische Polizei (später: Geheime Staatspolizei, Gestapo) um. Das Personal wurde fast geschlossen übernommen, die Zahl der Mitarbeitenden aber auch durch Neueinstellungen und Versetzungen nach und nach erhöht. Der Umzug der Bayerischen Politischen Polizei in das Wittelsbacher Palais im Oktober 1933 dokumentierte auch äußerlich die Eigenständigkeit der Behörde. Das Wittelsbacher Palais wurde bald zum Synonym für den gefürchteten Gestapo-Terror. In der Münchner Polizeidirektion selbst wurden nach der Machtübernahme nur wenige personelle Veränderungen vorgenommen, vor allem in der Führungsspitze. Alle leitenden Stellen wurden mit politisch zuverlässigen Beamten besetzt. Auch Himmlers Nachfolger als Münchner Polizeipräsident, SA-Obergruppenführer August Schneidhuber, setzte diese Personalpolitik fort.

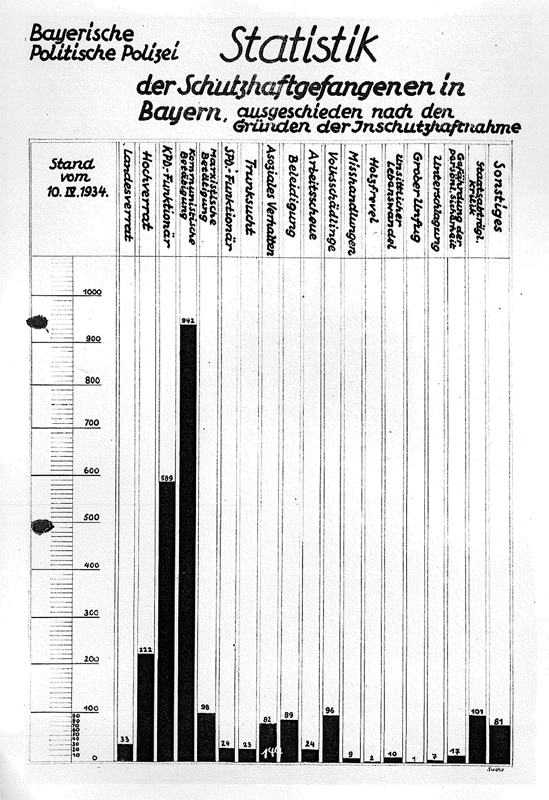

Um einen möglichen Widerstand von vornherein auszuschließen, etwa einen Generalstreik wie 1920 beim Kapp-Putsch, wurden Angehörige von SA, SS und „Stahlhelm“ zu Hilfspolizisten ernannt. Sie unterstützten die Polizei bei den sofort einsetzenden Massenverhaftungen und gingen dabei mit großer Brutalität vor. Sie demütigten und misshandelten ihre Opfer und beglichen „alte Rechnungen“ aus der „Kampfzeit“. Politische Gegner*innen wurden in „Schutzhaft“ genommen. Dies bedeutet, dass sie keinem Richter vorgeführt werden mussten, keinen anwaltlichen Beistand hatten und ihre Haftdauer keiner Befristung unterlag. Rechtliche Grundlage für die Schutzhaft war die „Reichstagsbrandverordnung“ vom 28.2.1933, die alle verfassungsmäßigen Grundrechte außer Kraft setzte. Weil die Gefängnisse nach wenigen Tagen überfüllt waren, verkündete Himmler schon am 20.3.1933 die Einrichtung eines Konzentrationslagers vor den Toren der Stadt. Es war explizit für Funktionäre der KPD, der SPD und des Reichsbanners vorgesehen, die auch die große Mehrheit der Verhafteten bildeten. Schon bald wurden aber auch andere Gegner des Regimes dorthin verschleppt.

Das KZ Dachau – Modell für das Reich

Das KZ Dachau gehört zu den ersten und größten Konzentrationslagern im Deutschen Reich. Anfangs stand es noch unter Bewachung der Bayerischen Landespolizei, die nach Himmlers Auffassung aber die Häftlinge zu nachsichtig behandelte. Im Mai übernahm auf seine Weisung die SS die Bewachung des Konzentrationslagers, das damit vollkommen seinem Einflussbereich unterlag. Sofort begann der Terror gegen die wehrlosen Häftlinge, schon im April wurden die ersten ermordet. Staatsanwaltschaftliche Ermittlungen wurden durch Himmler verhindert. Die organisatorische Dreiecksbeziehung: SS – Gestapo – Konzentrationslager gab es zuerst so nur in Bayern; diese Konstruktion wurde zum Modell für das KZ-System im gesamten Reich. Vor allem diente Dachau als zentrale Ausbildungsstätte für die SS-Wachmannschaften. Viele KZ-Kommandanten im Deutschen Reich begannen ihren Dienst im Konzentrationslager Dachau.

Die Polizei der „Hauptstadt der Bewegung“ als Karriere-Sprungbrett

Für Himmler und Heydrich, die Führer der SS, bedeuteten die Münchner Ämter einen enormen Schritt bei ihrem Aufstieg zu den zentralen Architekten des NS-Terrorapparates: Himmler wurde nach und nach in allen deutschen Ländern zum Politischen Polizeikommandeur, zuletzt auch in Preußen. 1936 gewann er den Machtkampf gegen Reichsinnenminister Wilhelm Frick und wurde Chef der gesamten deutschen Polizei. Heydrich übernahm im April 1934 das Geheime Staatspolizeiamt in Berlin und wurde später Leiter des „Hauptamtes Sicherheitspolizei“ (1936) bzw. des Reichssicherheitshauptamtes (1939).

Voraussetzung dieses rasanten Aufstiegs der SS war die Entmachtung der SA. Sie war im Frühjahr 1934 mit ca. 4,5 Millionen Mitgliedern ein bedeutender Machtfaktor geworden. Einige ihrer Führer waren unzufrieden mit den Ergebnissen der Machtübernahme und erstrebten eine „Zweite Revolution“. Um die SA zu schwächen und sich das Wohlwollen der Reichswehr zu sichern, ließ Hitler am 30.6.1934 die SA-Führung wegen angeblicher Putsch-Absichten verhaften. Dabei spielten Himmler und Heydrich eine zentrale Rolle. Ernst Röhm und andere SA-Führer wie auch Münchens Polizeipräsident August Schneidhuber wurden erschossen. Mindestens 90 Personen fielen der sogenannten Röhm-Affäre zum Opfer, darunter auch Regimegegner.

Zahlreiche Münchner Gestapobeamte, die ihre Karrieren sämtlich in der Polizeidirektion München begonnen hatten, folgten Heydrich nach Berlin und bekleideten hohe Positionen im NS-Terrorapparat. Unter ihnen befanden sich langjährige NS-Sympathisanten wie Josef Meisinger oder Reinhard Flesch, aber auch konservativ-katholisch geprägte Beamte wie Franz Josef Huber und Heinrich Müller, der sogar Chef der gesamten Gestapo wurde.

Polizei im NS-Staat

Der Charakter der Polizei änderte sich im NS-Staat grundlegend. Geschützt wurde nicht mehr das Individuum vor Übergriffen Dritter. Aufgabe der Polizei war nun der Schutz der nationalsozialistischen „Volksgemeinschaft“, aus der nach und nach verschiedene Gruppen aus politischen, sozialen oder rassistischen Gründen ausgeschlossen wurden. Im Sinne einer rassistisch-völkischen Generalprävention erhielt die Polizei neue Instrumente zur „vorbeugenden Verbrechensbekämpfung“ und durfte auch Verdächtige und Vorbestrafte in Polizeihaft nehmen und in Konzentrationslager einweisen.

Die Gestapo war die treibende Kraft im Kampf gegen die „Volksfeinde“. Doch von Anfang an waren alle übrigen Polizeisparten als Zuträger und Erfüllungsgehilfen an der Verfolgung der Gegner*innen des Regimes und solcher Menschen, die dafür gehalten wurden, beteiligt. Die Nationalsozialisten bemühten sich um eine Zentralisierung des gesamten Polizeiapparates („Verreichlichung“). Dies sollte die einheitliche ideologische Ausrichtung der Polizei ebenso sicherstellen wie die von Himmler angestrebte Verschmelzung der Polizei mit „seiner“ SS zu einem „Staatsschutzkorps“. Diese Verschmelzung schritt besonders bei Gestapo und Kriminalpolizei, seit 1936 zur „Sicherheitspolizei“ zusammengefasst, rasch voran, wurde aber nie vollständig erreicht. Alle Münchner Gestapochefs, und ab 1936 alle Chefs der Kriminalpolizei, waren Angehörige der SS, immerhin auch drei von fünf Polizeipräsidenten.