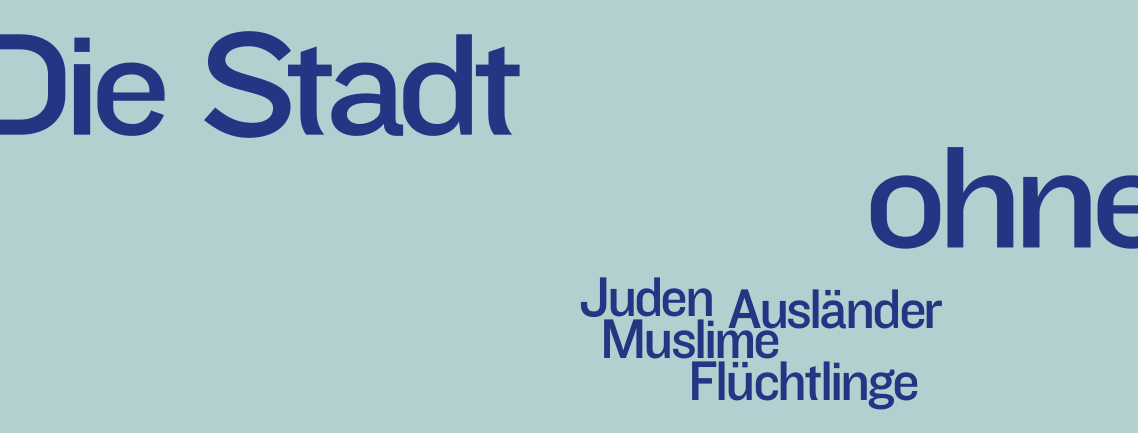

The main part of the exhibition examined the mechanisms that a majority society uses to exclude a minority. It traces the stages in the process of exclusion, introducing each of them with a scene from the film: from the polarisation of society to stereotyping, a loss of empathy and brutalisation to the complete exclusion of a group of people cast as the enemy. The exclusion process was illustrated with examples from history – starting in the 1920s – but the exhibition also used more recent examples to trace developments from the immediate post-war era to the present. Whereas in the 1920s, antisemites called ever more loudly for the exclusion of the Jews, today such calls are directed at foreigners, Muslims, refugees and, as in the past, Sinti and Roma. The City Without used this juxtaposition to pose the central questions of our age: Are we reliving ‘Weimar conditions’? Is the current situation similar to that at the end of the Weimar Republic, shortly before the Nazis came to power? Is there still time to warn people to ‘nip racism in the bud’?

The exhibition showed the continuity in antisemitic stereotypes and images of the ‘other’. Even before the Nazis came to power, election posters, publications and stickers made ‘the Jews’ scapegoats for lesser and greater evils. The first anti-Jewish pogroms took place in Berlin in 1923, but these were to be only the prelude to the ‘Jews out’ policy of the Nazis. Eugenics, the theory of promoting ‘healthy genes’ by ‘eliminating’ ‘foreign genetic material’, led to an increasing loss of empathy in the 1920s and 1930s. Today, people still look for ‘simple solutions’ for complex problems and allegedly find them in slogans like ‘foreigners out’. Whether it is criminality, sexual violence, disease or drugs offences, it is always ‘others’– Muslims, refugees, foreigners or Jews – who are blamed. Even the enemy stereotypes have remained much the same: images like a ‘blood-sucking spider’ or a ‘greedy capitalist’ are still used to portray ‘the Jew’. Today’s targets of discrimination include not only Jews, but also Muslims and particularly the refugees who arrived in Germany in 2015, with right-wing parties urging their exclusion from ‘German society’. The calls for ‘Islam-free schools’ in the election campaigns of the Alternative for Germany (AfD) party bring to mind analogies with the Nazi desire to make Germany ‘free of Jews’.

The exhibition concluded with a return to satire – the device used by Bettauer in the novel/film The City without Jews – in a section featuring the ‘container action’ Please love Austria staged by Christoph Schlingensief in 2000. In what was to become a political and public provocation, Schlingensief built a container village next to the Vienna State Opera with the words ‘foreigners out’ prominently displayed. Twelve asylum-seekers lived in the containers for a week, monitored by camera. In a play on the Big Brother TV reality show, each day members of the public could vote on which asylum seeker should be expelled from Austria. The action sparked heated debates and caused considerable confusion. Today, container villages for refugees and asylum-seekers are an everyday sight.