About the exhibition

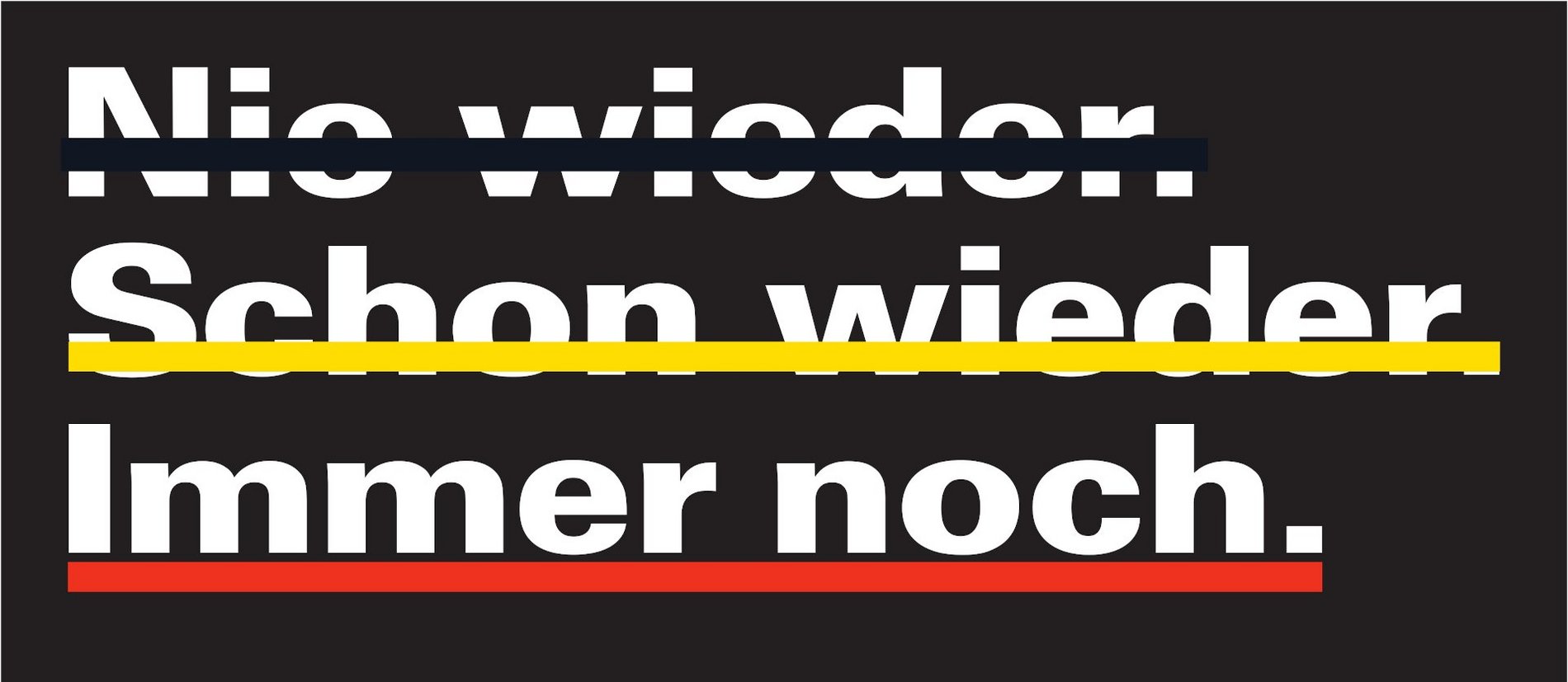

The murders committed by the terrorist cell National Socialist Underground and the attacks on asylum-seekers' accommodation and on refugees have once again increased public awareness of the issue of right-wing extremism and right-wing extremist violence. Right-wing populist parties are fomenting xenophobia, while supposed ‘patriots’ are stepping up to ‘save the West’ and are contributing to a general increase in crude language and modes of thought.

The exhibition addressed these developments and showed the place they occupy in history and in society. It traced right-wing populist, right-wing radical and right-wing extremist actors, organisations and parties from the immediate post-war period to the present day. Using authentic documents as examples, most of them from Munich and Bavaria, it illustrated the activities – including acts of violence – of members of the right-wing spectrum. A separate section of the exhibition devoted to right-wing extremist ideology explained the anti-democratic and hostile elements of this view of the world, including racism, social Darwinism and national chauvinism. The exhibits elucidated the strategies and methods used to disseminate right-wing extremist ideology and looks at the extent to which it has infiltrated mainstream society. The exhibition also surveyed the – frequently inadequate – democratic opposition to the activities of the extreme right.

The exhibition was realized in cooperation with Fachstelle für Demokratie der Landeshauptstadt München and Antifaschistische Informations-, Dokumentations- und Archivstelle München e. V. (a.i.d.a.).