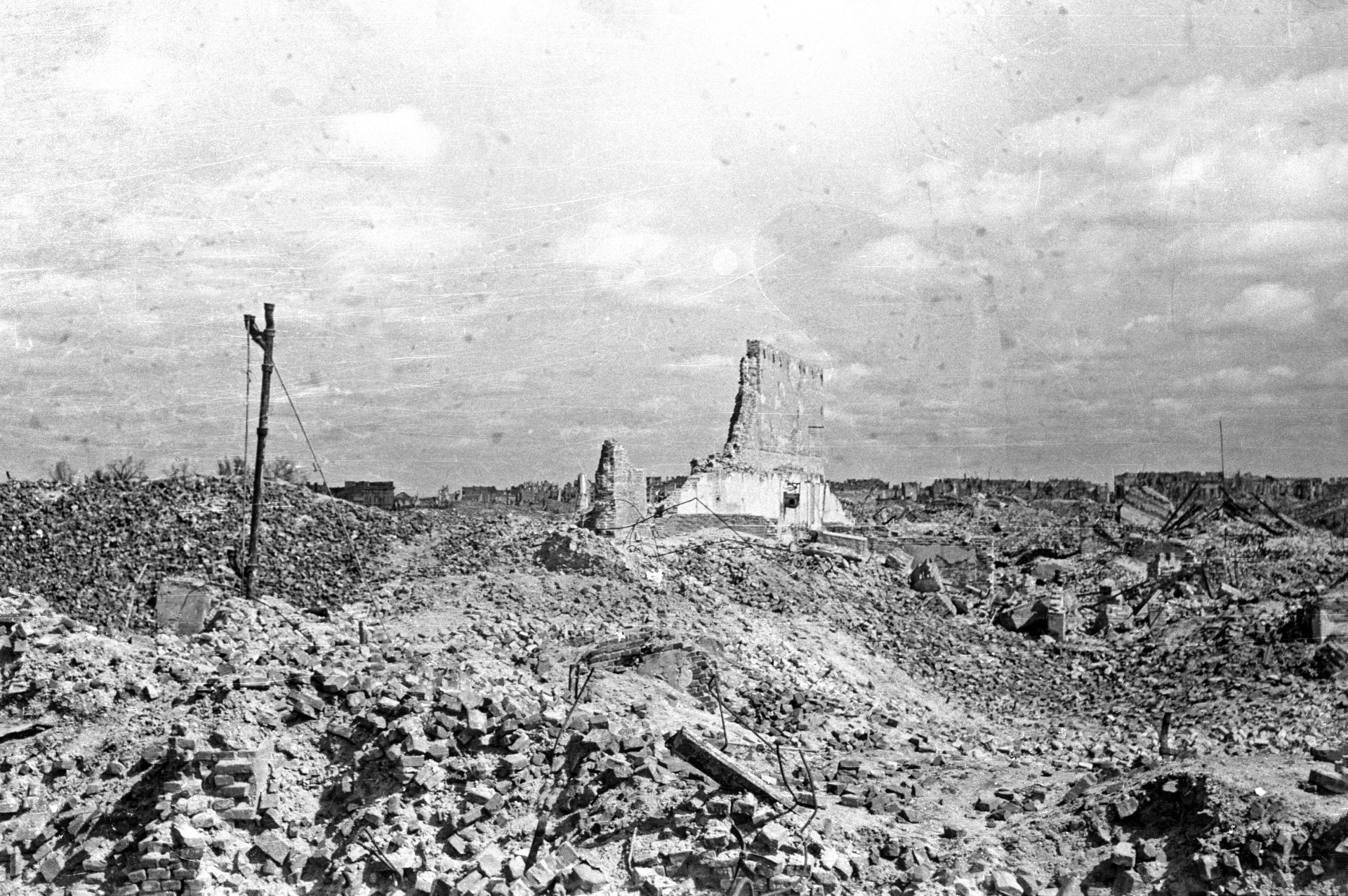

The subterranean city that is the former Warsaw Ghetto will not permit itself to be forgotten. It relinquishes reminders of itself every time construction machines involved in urban development projects strip away the covering shell of concrete and asphalt, revealing the outlines of houses and the old cobblestone routes of that city – the city that existed before 1939 – 1945. Signs of the old life vexingly transpire among the bulldozers’ excavations.

That life was terminated abruptly, crushed, burned. What remains – aside from glimpses of memories – are fragments of things that the property development companies would like to swiftly eradicate, or at least cover up once again. But the relicts themselves cannot be compromised. They call on artists, writers, museums and other institutions of memory to bear witness to the destruction of that world in its entirety – so that we may witness it with our own eyes.

There are in fact two facets to this ruined urban landscape – the Polish one, and a space within it, designated as Jewish. From 1940 to 1943, the two were divided by a wall, built on German orders, whose purpose was to separate Jews from Poles. The former, as “Lebensunwertes Leben”, were doomed to slow agony and eventually a sudden, torturous death; the latter, whose selective extermination was depriving them of their elites and of the power to resist, were to be relegated to the categories of the subhuman and reduced to a labor force. Both facets are marked by death and a funereal substratum of urban memory, and yet are infused by these to varying degrees. Not least because the ghetto area became a total cemetery.