1 Michaela Dudley, Race Relations: Essays über Rassismus, Bad Lippspringe 2022, S. iii. See also p. 166

2 Ibid. See also Michaela Dudley, Marathonlauf der Mehrfachdiskriminierung, in: das goethe, Kulturmagazin des Goethe-Instituts (supplement in: Die Zeit), 2022/1, p.22

3 Siehe Kimberlé Crenshaw, On Intersectionality: Essential Writings, New York 2017

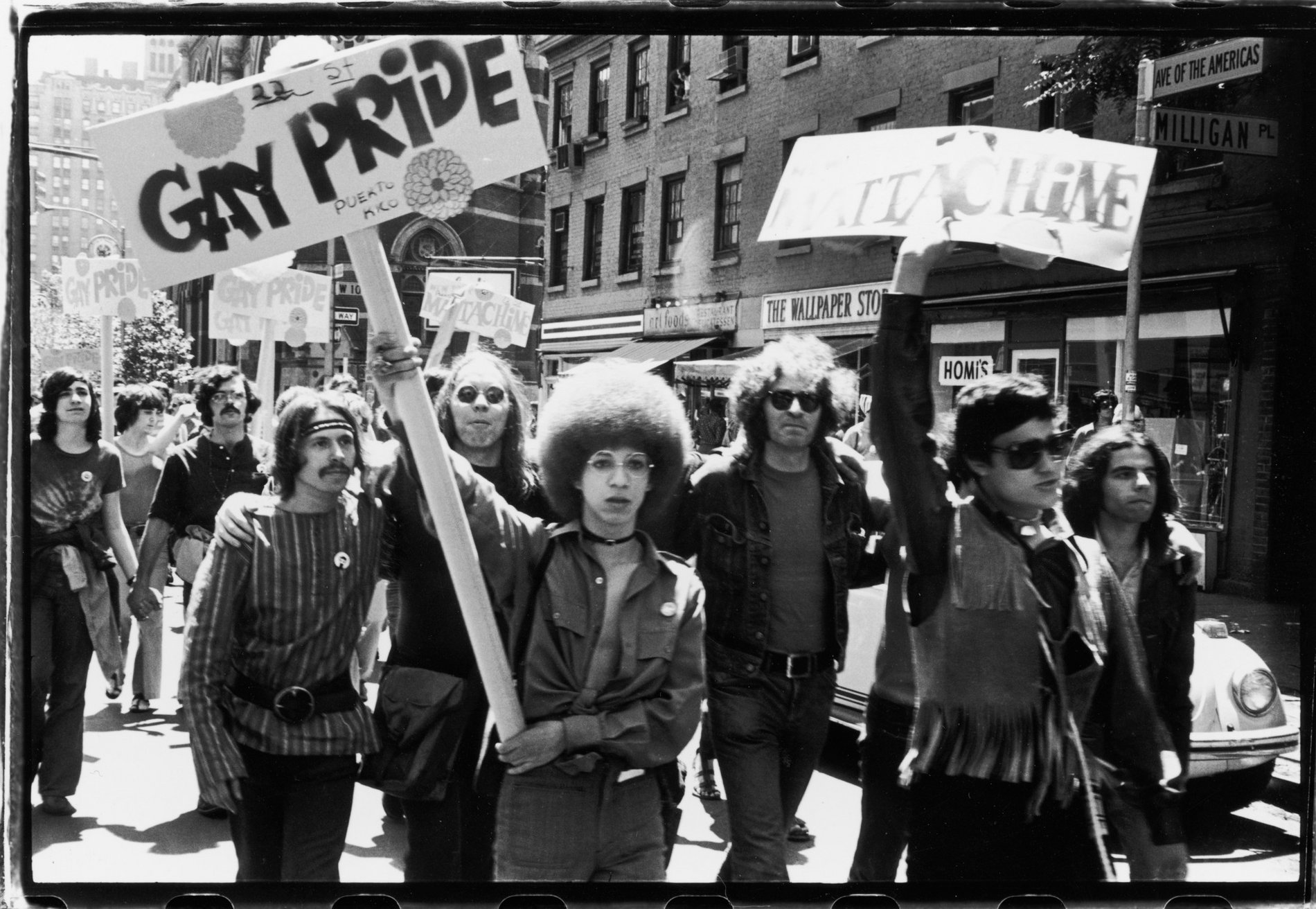

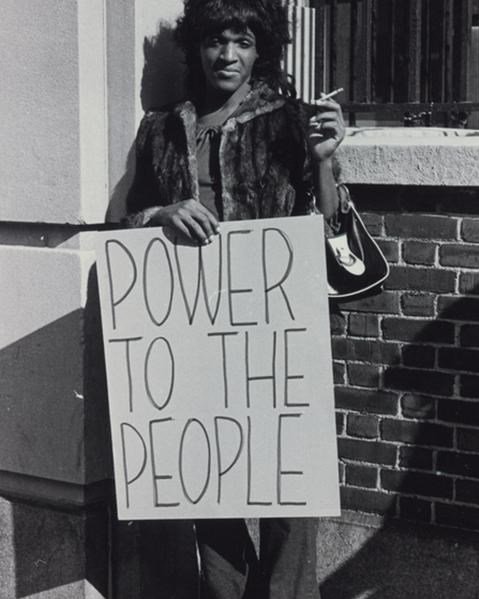

4 Michaela Dudley, Und sie warf den ersten Stein von Stonewall, in: Glitter – die Gala der Literaturzeitschriften, 2020/4, S.27–34.On this, see the musical homage Michaela Dudley, “Owed to Marsha,” GEMA work number 24392279, transmitted by Kulturzeit, 3sat-Fernsehen, Mainz (first performed on August 25, 2021).

5 Arndt Peltner, Manche starben im Gottesdienst: AIDS und Religion in San Francisco, in: Deutschlandfunk Kultur [accessed April 24, 2022]

6 Michaela Dudley, Wie wollen wir leben?, in: TAZ [accessed April 28, 2022]

7 Sonja Thomaser, „Don’t Say Gay Gesetz“-Gesetz: Disney-Erb:in outet sich als trans, in: Frankfurter Rundschau [accessed April 22, 2022]

8 LGBT-Rechte weltweit: Wo droht Todesstrafe oder Gefängnis für Homosexualität, in: LSVD [accessed April 22, 2022]

9 Ibid. See also Lucas Ramón Mendas u.a., ILGAWorld, State-Sponsored Homophobia: Global Legislation Overview Update, Genf 2020

10 Tagesschau, Diskriminierung: EU geht gegen Ungarn und Polen vor, in: Tagesschau, 15.7.2021 [accessed July 21, 2021]. Parallel with TV report by Astrid Corral, NDR Brussels.

11 Ibid.

12 Deutsche Welle, Queer Balkan – Im Kampf um gleiche Rechte, in: DW [accessed April 11, 2022]

13 Michaela Dudley, Jubel, Trubel, Heiserkeit, GEMA-Werknummer 20909652

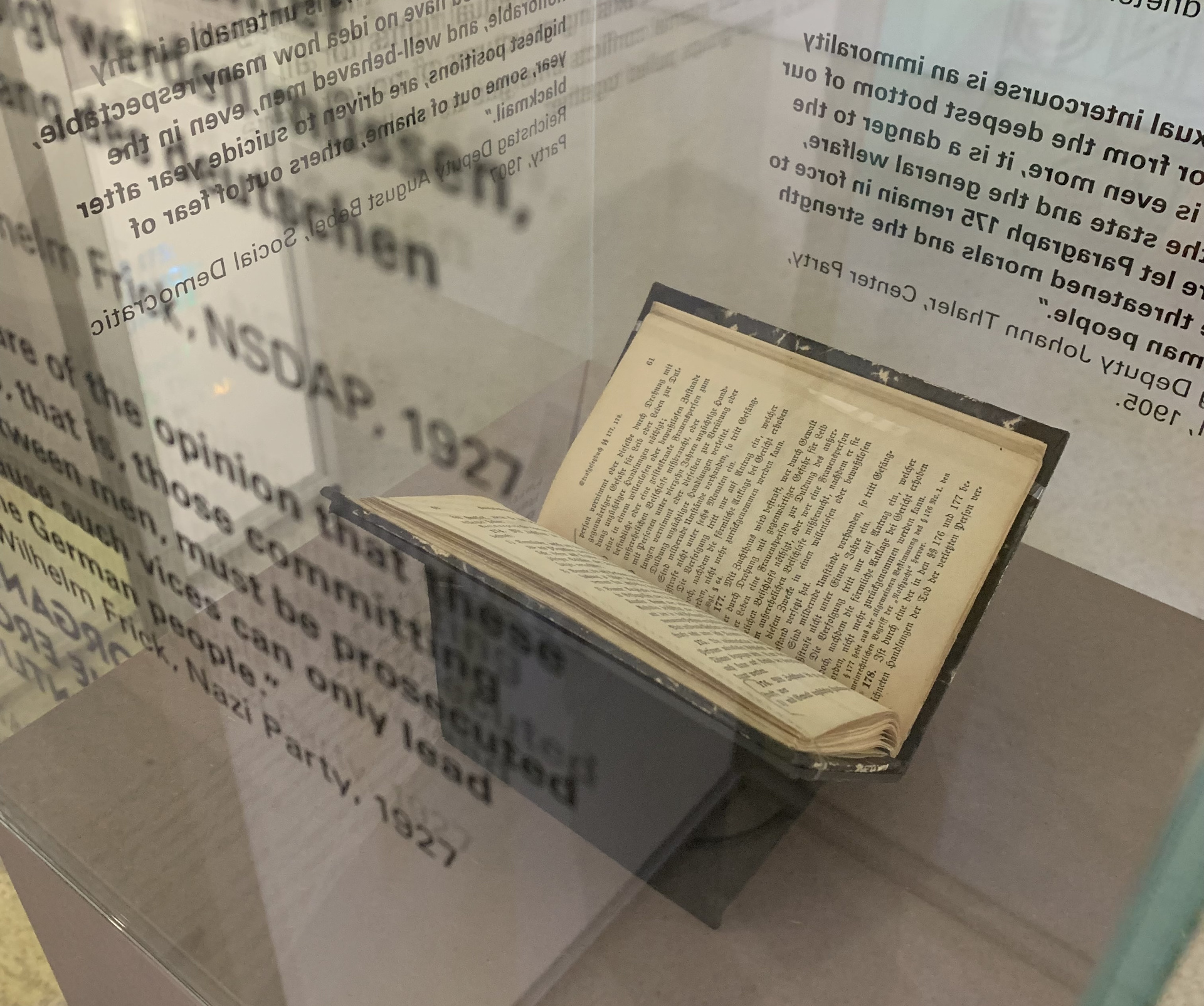

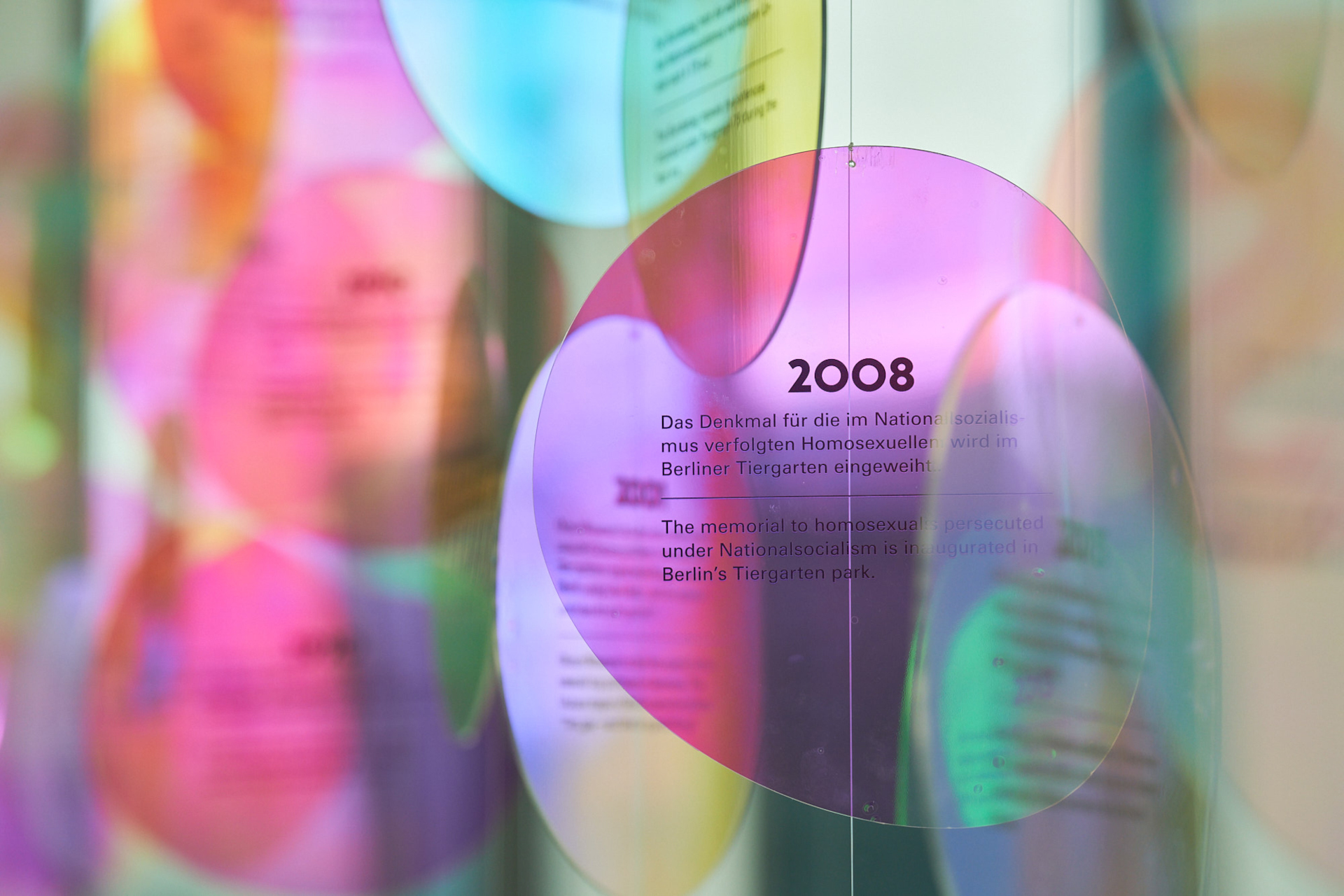

14 Michaela Dudley, Der Tanz auf dem Vulkan: Berlin in den Goldenen Zwanzigern, in: taz [accessed May 20, 2022]

15 Michaela Dudley, Der Regenbogen und die Wolken, in: Veganverlag [accessed May 20, 2022]

16 Ibid. See also Laurie Marhoefer, Lesbianism, Transvestitism, and the Nazi State: A Microhistory of a Gestapo Investigation, 1939–1943, in: The American Historical Review, 2016/121, S. 1167–1195 [accessed March 4, 2022]

17 Stiftung Brandenburgische Gedenkstätten, Mahn- und Gedenkstätte Ravensbrück, Gedenkzeichen für die lesbischen Häftlinge im Frauen-Konzentrationslager Ravensbrück [accessed May 12, 2022]

18 Andreas Pretzel, NS-Opfer unter Vorbehalt: Homosexuelle Männer in Berlin nach 1945, Berlin u.a. 2002, S.306f. Siehe auch Gottfried Lorenz, Homosexuellenverfolgung in Hamburg, Ausstellung Staatsbibliothek Hamburg, 27.2.2007

19 Jacob Poushter und Nicholas Kent, The Global Divide on Homosexuality persists, in: Pew Research Center [accessed May 28, 2022]

20 See note 6.